![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

5/7/2016

![]()

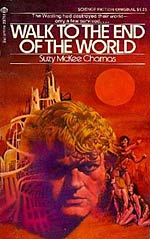

There's going to be a lot of defensive denial from readers who look upon my copy of Walk to the End of the World(1974) by Suzy McKee Charnas with "The terrifying science fantasy about a world ruled by men" blurbed on the cover. Knee-jerk responses will vary from "pshh, that's not fantasy, that's reality" to "that would never happen this author is a man-hater." The cover image of an enslaved woman kneeling before two stern-faced men is equally contentious. (cover below, for I could not bear to make it the lead image for this post. this red one over here isn't much better.)

So let's take a moment to readjust our worldview: Systemic slavery of women exists today, in larger numbers than you think. It exists in first-world countries, with an estimated 60000 slaves in the US, most of them women. Even conservative states in the US are taking action, explicitly designating Human Trafficking Task Forces to differentiate from smuggling and immigration issues, while educators are being trained to identify victims of slavery, just as they do victims of child abuse and neglect. Moreover, areas of economic boom have the highest rates of slavery in the first world.

And no matter where you find it, or in what form, slavery today is overwhelmingly gendered, with men subjugating and controlling women against their wills, all over the world.

Even with all that data, it's still going to be difficult for some readers to accept the premise of Walk to the End of the World. And Charnas doesn't help: she isn't about to coddle those readers who wander beyond the cheesy cover for a first page skim:

Women had not been part of the desperate government of the times; they had resigned or had been pushed out as idealists or hysterics. As the world outside withered and blackened, the men thought they saw reproach in the whitened faces of the women they had saved and thought they heard accusation in the women's voices...

...They forbade all women to attend meetings and told them to keep their eyes lowered and their mouths shut and to mind their own business, which was reproduction.

...A few objected, saying, no, these men will enslave us if we let them; no one is left to be their slaves except us! They tried to convince the others.

The men heard, and they rejoiced to find an enemy they could conquer at last... (3-4)

Some of the best SF stems from incendiary doomsaying seeded by contemporary observation: Brunner's overpopulation, Ballard'sevolutionary regression, Tiptree's screwfly men. The point of this kind of speculative fiction is not to predict or promise direct parallels, but to illustrate a point about society. But while the extreme dystopias of Brunner and Ballard are hailed by a wide audience of readers, the extreme dystopias of Tiptree and Charnas are often dismissed, or treated as dangerous and exaggerated, as if the same higher-thinking skills that are required to parse out the significances of Brunner's and Ballard's hyperbole cannot be applied to feminist SF. Joachim Boaz comments on this same double standard in his own excellent review of this same novel.

In Charnas' far-future, post-apocalyptic world, all nonwhite persons have been wiped out, and dissenters have been either exterminated or subjugated. Men not fitting the acceptable macho profile have been bred into nonverbal beasts of burden. Women are kept as chattel, assigned to hard labor, reproductive labor, servitude to male society. Interestingly, both male and female societies have become homosexual in the process: for men, sexual relations with the "fems" is nothing more than an unpleasant reproductive duty, occasional curiosity, or assertion of power.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of this novel is where Charnas drops us: right in the middle of the far-future, long after the tumult of nuclear crisis (assuming), where the destruction of society as we know it is in the distant past, and the subjugation of "fems" has long been established. The status quo is unrecognizable to readers. It's a quiet violence in a way, more revolting than brutal in its details, because the women in this story were born into this society, the rebels wiped out or bred out long ago. Obedience is the norm, any signs of unrest will be covert, underground. There is no protest. Not even clenched jaws.

Which makes it difficult to orient to this book, where the fems are even oppressed by the narrative. It's a man's world, after all, therefore the lens is on the men -- so unlike popular feminist SF that centers directly on women protagonists, no matter how gnarly the contrivance (ahem, The Handmaid's Tale, with your epilogue about "discovered tapes" that couldn't possibly exist in a world of women without property). It's an unexpected turn, the way the men's stories, with their petty politics and soap opera affairs, dominate the tale, meanwhile the reader's eye keeps glancing about the periphery of each scene, looking for women -- or any sign of the real struggle. When Alldera, clearly the hero of the tale (right? right?), enters the picture on page 77, she is without tights, tricks, or tumbles. She's not even pretty:

She turned up toward him a face like a round shield of warm metal. Instead of the sweet perfection of Kendizen's pets, this fem's face expressed a willful stupidity that was perfect in its own way. The muscles around the wide mouth were strongly molded and the lips cleanly edged, but instead of mobility the effect was one of obstinate dullness. Her eyes, not large enough for the breadth of cheekbone underneath, gazed blankly past his shoulder; she blinked only after a long interval, and sleepily. The total impression given was one of fathomless unintelligence. (117)

Charnas borrows a lot from the era of American slavery, the tone and behaviors strikingly similar to that of slave narratives from the plantation-era South. When Walk finally opens up to the real story, Alldera's POV in the penultimate section on page 159 of 246, we are finally enlightened to the fems' strife on their own terms, those quiet, covert rebellions that slaves have relied on historically: pidgin and linguistic drift, chants and songs, work slow downs and playing dumb, strengthening community in isolation. Alldera's section reveals all of this, undermining the previous half of the book, the men's soap opera part, by unveiling the workings of her mind, as well as more of this world we've been trampling through, while still participating in the overall story arc: the men's quest to get from A to B. In many ways, this revelation mocks the first half of the book, along with any and all other male-driven quest fiction that keeps women on the side.

Not that the first half of the novel is entirely intended for just the purpose of mockery. Walk to the End of the World is foremost a study of character, an ongoing demonstration that rigid social barriers serve no reality, the internal workings of men and women are much too knotty. Each male character, seeming petty at first, is complex and dynamic, not a good fit for the strict roles and expectations within the Holdfast hierarchy. At a witch burning:

Bek flinched at the sight of them. He had always had that reaction, an involuntary sympathy rooted deep in the body-brute. He forced himself to look again. (128)

This is the feminism, root words be damned. Charnas uses the men's complexities in Walk primarily to highlight the perversion and failure of strict gender and social roles.

Most fascinating is how all aspects of this society are tied together by flimsy Oedipal superstitions. "Rebellious sons rise...to strike down first their fathers' ways, then their fathers' lives" (145). These superstitions drive the plot, the reason for female slavery, the reason for the A-to-B questing, as well as explain so many of the odd incongruencies between Holdfast society and our own. It's an achievement that Charnas can make it work: to saturate this society with Oedipal paranoia, to establish it as the foundation of a viable system, while maintaining that sense of irrationality and flimsiness in the reader's eyes. It's an impressive bit of social architecture.

As a novel, Walk to the End of the World is a fascinating study of world building and intention, though not ideal for a casual, weekend read. The depiction is strong, revolting at times. Some will find discomfort with the quite literal PoC-erasure, which (though supported by the plot) feels limiting and amputated with its constant men/women dynamic that's really a white men/white women dynamic that often goes unacknowledged. Though well-layered character is its strongest aspect, the dialogue and action are not well-incorporated into the narrative, giving it a broken, jumpy feel that can't always be intentional for fostering a fragmented tone. It is a difficult read, both for its layered subtleties and because, well, it is a character-driven science fantasy (which is hard enough to read) that's a vehicle for something more, making it similar to the experience of reading The Book of the New Sun, Viriconium, and, more recently,Glorious Angels. Deep, patient reading is required.

Had I planned my reading better, and had a stronger stomach, I would have paired Walk to the End of the World with something from the Gor series, a popular fantasy series based in a world of male domination and female enslavement -- just to remind myself when those protestations kick in that there really is a desire out there for this kind of reality.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com