![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

10/15/2015

![]()

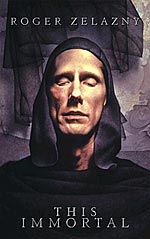

I feel like this book should really be called ...And call me ...And Call Me Conrad. Sort of like that Gene Wolfe collection, The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories.

To be honest, I much prefer the publisher's title. This Immortal just feels more ripe. It certainly makes for a more interesting lens. But Zelazny wants us to call it [pause]...And Call Me Conrad. So we must. And with that, the lens becomes less focused on this immortal, (as in, not those immortals, which would make for some fun comparisons) and more focused on this dude with 'tude. Whose name isn't really Conrad, but by golly we better call him that.

...my left cheek was then a map of Africa done up in varying purples, because of that mutant fungus I'd picked up from a moldy canvas... my eyes are mismatched. (I glare at people through the cold blue one on the right side when I want to to intimidate them; the brown one is for Glances Sincere and Honest.) (loc. 69)

My right eye is the one over which I furrow my brow. People say it's intimidating.

Confounded by my withering experience with Roger Zelazny's 1965 fix-up - a novel and author I was sure to love-- I went to the experts to find out what I'm overlooking:

"an impressive disappointment," (F&SF, Dec. 1967, 34) - Judith Merrill

"stodgy and undigested" myth... "in need of a good editor..." (Trillion Year Spree, 2001, 337-338) - Brian Aldiss and David Wingrove

"no real plot..." (F&SF, Jan. 1968, extracted from The Country You Have Never Seen, 2007, 6) - Joanna Russ

Okay, so maybe I'm not such an outlier. But then we have Delany over here:

"The wonder of the prose is that it manages to keep such intensely compressed images alive and riding on the rhythms of contemporary American."- Samuel R. Delany (The Jewel-Hinged Jaw, 2009, 52)

Well, that's true, too, and I love the crisp, vivid tightness. But it's the other stuff that gets me. It's not that the contemporary American prose isn't so contemporary anymore, it's that I'm tired of this jaded, unaffected arrogance we see so often in male protagonists:

"What's she like?"

I shrugged.

"A mermaid, maybe. Why?"

She shrugged.

"Just curious. What do you tell people I'm like?"

"I don't tell people you're like anything."

"I'm insulted. I must be like something, unless I'm unique."

"That's it, you're unique." (loc. 181)

For the history buffs, [pause]...And Call Me Conrad tied with the more famous Dune for the Hugo Award in 1966. In terms of writing, [pause]...And Call Me Conrad is far better than the prosaic and clumsyDune. Where Herbert resorts to italicized internal thoughts to convey nuance and depth (an oxymoronic technique if there ever was one, she thought to herself), Zelazny lets his protagonist's sardonic wit do the talking (while the reader does all the sorting of bullshit).

"'Mine won't bother people, just spiderbats. They discriminate against people. People would poison my slishi' (He said "My slishi" very possessively.)" (loc. 421).

Zelazny is funnier than Herbert, too.

So back to the question of what bothers me about this book: It's another detached, unaffected first-person male narrator. At a cursory glance most people love This Immortal, not for its understated dynamism or the unsprung symbolism that Delany points out, but for its chilled-out, don't-mess-with-me-man god protagonist, apparently a blueprint for what will become a standard Zelazny character (oh great, more disaffected, entitled dudes, she thought sarcastically). It's a model that's common in SF, almost like a rite-of-passage for authors to play with--that hard-boiled detective style. So then I wonder, why doesn't it bother me in contemporary SF that I love, such as Lavie Tidhar's Osama (2011) or China Mieville's The City & the City (2009), or more recently in Dave Hutchinson's Europe in Autumn (2014) (which is more Le Carre than Chandler, but it's still full of unshakeable white dude 'tude). Is it because the contemporary concerns (terrorism/alienation/immigration, or, rather, borders/borders/borders) addressed by those books feel relevant enough to me today to override the gnawing machisimo? Or, perhaps the Tidhar/Mieville/Hutchinson protags are uncertain enough about their circumstances to not come off as disaffected know-it-alls?

(It's probably the borders thing, frankly, and I just realized how very one-dimensional I am with my Texas residency, Latin American studies degree, and NAFTA-imported husband.)

But much as Delany exhalts Zelazny's Archimedean archetype--a man so intent on his insight that he sees little of the surrounding world-- and what he calls poetry (and I call economical wit, because, while Zelazny describes things in a tight, pretty way, Delany himself far surpasses him in beauty and affect), it's just another unwieldy fantasy adventure with lots of monsters popping up (which Vance had long ago already made fun of), and what Merrill refers to as another response to "myth-loss." She describes the tale as "last night's champagne in today's plastic flask," though to her, the plastic is the "lost the power of myth," whereas to me, the plastic is the Chandleresque mode of voice. (Merrill finds this style revolutionary. Fifty years ago, mind you.)

But I have to side with Merrill one this one, despite Delany's sermonizing. Delany knows his shit, but that just makes me want to read more Delany for poetic prose, structural symbolism, and subversive insight.

And back to the popularity of the stiff upper lip protagonist, it's a fine way to gain a reality-puncturing perspective on the surrounding world, and even, at times, it provides for surprising self-awareness, but the swarthy "I got this" component will only plumb character depths as far as the upturned leather jacket collar.

Konstantine-- I'm sorry-- Conrad is a man who's got it all figured out. He's got people pegged. He's got you pegged. He's got his friends pegged:

...and the expression that had once lived in that flesh covering his skull had long ago retreated into the darkness of his eyes, and the eyes had it as they caught me--the smile of imminent outrage (loc. 218).

And he even knows himself; he'll tell you when he's sad (so distraught when he thinks his newlywed wife is dead, even though she doesn't know his last name or age. Immortals always go for the young, carefree chicks, you know.)

But he'll say he's distressed, and you won't actually feel it. This immortal will keep you at arms-length.

A true professional must respect some sort of boundary between self and task. (loc. 1063).

Oh shut up.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com