![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

6/9/2015

![]()

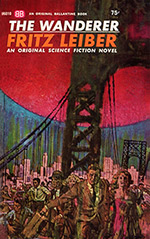

A predecessor to the disaster film genre, particularly the universally panned parody Disaster Movie (2008), where culturally-identifiable groups of people struggle, or amble, to survive against an uncontrollable, dangerous force. In the 1965 Hugo award-winning The Wanderer, Fritz Leiber introduces a sprawling cast of characters that spans the globe, while a UFP (unidentified flying planet) arrives in the sky and appears to consume the moon.

The shrewder souls thought: Publicity for a new horror film, or - aha--pretext for new demands on China and Russia. (ch. 14)

Every few years or so, some lazy publication like The Daily Mail or HuffPost will venture away from typical scare news tactics and post an article where some dingbat pseudoscientist forewarns the end of humanity due to X planet swinging round close enough to disrupt tides and shift tectonic plates. That's usually followed by an influx of commentary from celebrity scientists with social media platforms to debunk the articles with, er, science, and the whole tumult dies down and people quit worrying about space-influenced catastrophes, and go back about their business of having barbecues and ignoring rapid glacial melting.

Playing with that astrology-inspired premise of celestial-influenced disaster, The Wanderer brings to mind those sensationalist warning stories and does it in a way that evokes the tongue-in-cheek drama of a National Lampoon-style take on the disaster film genre. It's a fairly standard disaster plot, but with enough SFnal elements to evoke a few wondrous moments (e.g. rocketing through the middle of the moon as it splits in half), and with enough scientific elements to suggest that Leiber knows a thing or two about tidal forces and planetary distance. And if that doesn't sell it, there's also cat-person sex.

Science fiction is as trivial as all artistic forms that deal with phenomena rather than people. (ch. 1)

Like The Big Time (1958), Leiber's theatre background is present, primarily through characterization this time, where big personalities with names like Wolf Loner, Arab Jones, Barbara Katz, and Dai Davies maneuver within their own little microcosms while the macrocosm shifts and yields to greater forces. The personalities feel better designed for the stage: outrageous, two-dimensional, more stereotyped than nuanced. In The Big Time, this technique is less offensive as he sculpts his performers into historical depictions of a Nazi, a Roman soldier, and a cigarette girl, but it fails for modern readers of The Wanderer, where Arab and Pepe are the stoners, and a millionaire called "KKK" cusses out his Black servants.

But with a cast of over twenty characters in a meager 300-page book, Leiber has no time for nuance. His aim is multiculturalism-- a stodgy sixties version, sure-- and it succeeds in globalizing the feel of the disaster. And, frankly, the characters are fun--unforgettable-- particularly when the wild Sally and Jake climax at the top of a roller coaster during the arrival of the Wanderer, or when "KKK" wakes from his slow death long enough to admonish the local racists for threatening his Black servants.

All culture is but a sop to infant humanity. (ch. 1)

Most enjoyable, however, is Leiber's eloquent remarks on life ("the majority and the nuts spend most of their time the same way: satisfying basic needs" ch. 15.), including his extended metaphor of tidal music (ch. 21) and his eye-winking tributes to science fiction ("Either his escorts had the inertia-less drive at which everyone but science-fiction writers scoffed" ch. 19). It's in these moments that the substandard plot comes alive as a conscious tribute to the genre, rather than just a mediocre space spin on the disaster novel.

Certainty's a luxury. If you say things with gusto and color, at least you're an individual. (ch. 15). -- Gusto and color, that's so Leiber.

An unpopular Hugo winner among modern readers, I feel like this is a misunderstood book. It shows its age, but I don't think modern readers can enjoy or even appreciate Fritz Leiber's fiction without first recognizing Leiber's theatre background as a major presence in his work. When viewed from a theatre perspective, elements of parody and shtick arise where most might misinterpret substandard cliché. Combine that with his penchant for eloquence and heavy sci-fi elements, and its early arrival to the disaster sub-genre, The Wanderer is a worthy classic in the field.

Really, science fiction was corrupting people everywhere. (ch. 12)

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com