![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

5/2/2014

![]()

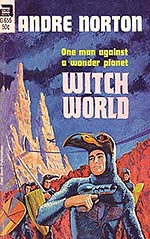

A book about an alternate world called Witch World? How puntastic!

...but he could not accept the atmosphere of this place as anything but alien. And not only alien, for that which is strange need not necessarily be a menace, but in some manner this place was utterly opposed to him and his kind. No, not alien... but unhuman, whereas the witches of Estcarp were human, no matter whatever else they might also be (p. 182).

How could two so widely differing levels of civilization exist side by side? ...Alien, alien—once more he was on the very verge of understanding—of guessing— (p. 171).

He never figures it out. At least, not in the first book of this expansive series.

And it's odd to the see the term "alien" pop up so repetitively in a magic fantasy novel about witches, but it was a term to which I clung out of the hope that something really cool or meaningful would happen. That's not to say I expected little green men to tromp around this world of witches (okay, maybe a little), but I hoped to extrapolate some deeper significance when considering the immigrant status of our good protagonist Simon Tregarth. It never happened.

Post-WWII, former soldier Simon finds himself wrapped up in some unsavory deals with dangerous folks. Now they want to kill him, but Dr. Jorge Petronius offers Simon the perfect, permanent hiding place in exchange for a large payment. Simon accepts the offer, goes through a door, and WHOOSH! He finds himself in an alternate universe where witches with vague and limited powers run the kingdom of Estcarp, which maintains unstable, often violent relations with at least five other provinces, including an evil, mysterious land beyond the sea. After weeks or years (I've reread this part a dozen times and I still can't tell) Simon assimilates to his new culture and becomes a guard for Estcarp. His band of soldiers attack an enemy, then another, then another. There's a big ship wipeout, and a cave, and some Falconers, and these zombie bird-men, and maybe some machines... that's the alien part, I think.

And if you want to incapacitate a witch, and you haven't any buckets of water, you can just rape her. Because a woman's power is in her purity.

It's possible that Witch World dangles on the cusp of the feminist fantasy genre, sandwiched between the stale gender roles in works by T. H. White and J. R. R. Tolkein and the more subversive gender roles portrayed in works by Ursula Le Guin and Marion Zimmer Bradley. From Witch World, there is a small sense that Norton might attempt to do something different from her predecessors, which is why the most bothersome part of this novel is its absolute surrender to a dated worldview. It was a characteristic I was surprised to find in a sixties SF novel written by a woman, but an oversight that I think is corrected in the series' later novels. Still, knowing that makes this installment all the more unsatisfactory, as its truncated story could have continued in longer and possibly more satisfying form. An omnibus version of the first three books was published in 2003, perhaps to address this issue.

Regardless of Witch World's potential social statements, the treatment of female magic is unimaginative and disappointing. The witches demonstrate small, covert powers that are easily neutralized by sexual intercourse. I had hoped that fantasy had shed its chastity belts by 1963, but in Witch World, only pure, virginal women can possess these vague, magical powers, although it is hinted that Simon, the strange outworlder, might also have a knack for psychic hunches. (I wonder ifhe's had sex.) If a witch's purity is sullied, she is essentially castrated. A witch who chooses to marry, chooses to "[disarm] herself, put aside all her weapons and defences, given into his hands what she believed was the ordering of her life" (p. 222).

The unresolved ending and sudden (oh, so sudden!) romantic tangles, which challenge the Estcarp status quo, indicate that the Witch World series has the potential to shed these antiquated worldviews, but not enough seeds are planted to convince me that challenging social roles was part of Norton's original agenda. It's common for even celebrated fantasy novels to embrace the rigid past and avoid social statements (beyond the "poor white boy becomes a hero" trope), but they make up for it in rich character development and tense plot movement—none of which happen in Witch World. Considering Norton's long publishing history, I expected better technique and concepts, and was disappointed by her stilted narrative style. The story failed to keep my attention, often requiring me to reread passages with greater intensity than usual, which heightened my notice of confusing sections. It was a chore to read, but it might be an adequate story for a child. I stopped after the first novel, but the omnibus version might prove to be more satisfying.And gender isn't the only thing that receives old-fashioned treatment. Koris, the Guard captain of questionable breeding and unique stature, is basically an over-muscled dwarf, to whom Norton often refers as "misshapen," "grotesque," and "ill-formed." These descriptors are not intended to be malicious, but communicate an ignorance that isn't acceptable in today's SF. Norton characterizes him with honor and respect, perhaps a "beauty on the inside" lesson, but it niggled my PC lobe. Beyond that, I was especially excited to discover a fantasy character named Jorge (a doctor of some kind, nonetheless!), only to be disappointed when his brief appearance involved underground dealing and scamming. Bummer.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com