![]() Scott Laz

Scott Laz

11/3/2013

![]()

Centuries from now, having survived worldwide nuclear devastation in underground shelters, people began returning to the surface as the Earth again became habitable. As the men and infertile women went out to explore, those women who remained behind in the shelters took on the responsibility of repopulation, making use only of men determined to be genetically undamaged. Believing that the destruction of the world was the result of male aggression, these women eventually moved inland and built new cities, protected from the outside by walls and force fields, and developed a matriarchal lesbian culture that maintained science and technology. Men were forced to remain outside in a primitive state, living in small bands and prevented from moving beyond Stone Age technology, having forgotten the truth of their own past, brought to the cities only to fulfill their role in in vitro fertilization. The women built a set of Shrines throughout the areas around the cities, where men could go to worship the "Lady"—their Goddess. In these shrines, men put on circlets that linked them telepathically to women in the city, who sometimes fed their minds erotic fantasies, and occasionally called them to the city for a "Blessing"—more virtual sex for the purpose of sperm "donation".

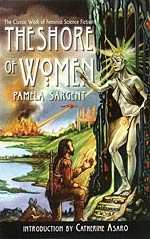

In The Shore of Women (1986), Pamela Sargent explores this divided world, which has been long established when the story begins. In the first third of the novel, the point of view moves back and forth from Laissa, a young women on track to become one of the "Mothers of the city"—the intellectual and political leaders who ensure that their way of life (and that of the men's outside) continues—and her twin brother Arvil, who lives outside with his guardian (and father, though the men have no knowledge of the workings of hereditary relationships). Like all boys, Arvil was expelled from the city at age five or six, his memory erased, his guardian called by the Mothers of the city to adopt him into one of the male bands. Laissa's narrative, and the story of the women in the city, breaks off somewhat disconcertingly, but is picked up again in the final chapter, where we discover that the chronicle we've been reading was actually written by Laissa, who later in life became a historian and chronicler. The viewpoint shift away from Laissa makes sense in light of the book's conclusion.

The story she and the rest of the novel tells is of Arvil and Birana (whose point of view alternates with Arvil's for most of the book). The first incident related by Laissa is the expulsion of Birana and her mother from the city. Birana's mother had attempted to murder her partner, while Birana refused to interfere, murder of one woman by another being the City's ultimate crime, and exile being the punishment. The Mothers will not contemplate execution, but fully expect that any woman sent outside the city will be unable to survive for long. And while Birana's mother is quickly killed by a band of men who don't realize what she is, Birana survives, using the men's worship of the "Holy Lady"—of which any woman must be an individual aspect—to get some of them to help her. One of these men is Arvil, who Birana, despite her "natural" revulsion for males, and belief that they are inherently animalistic, brutish, and stupid, will slowly begin to see more in him, and is forced to accept his protection in order to survive.

Birana knows that, if they find out that she survives, the women of the city will not allow her to continue to live, fearing (rightly) that she would reveal the real non-divine nature of the women in the city, and that her continued existence would have to eventually come to light when men who have seen her put on the telepathic circlets in the Shrines. So she embarks with Arvil on an eastward journey, hoping to find a fabled Refuge for women expelled from the cities, or at least get far enough away to be out of reach of the Shrines and the women's ships.

This set-up allows Sargent to pursue two related threads in the novel. First, as they travel, Birana and Arvil encounter and live with various bands of men, and Sargent explores a culture of men without women, which can be contrasted with the lives of the women without men in the cities. Birana's presence forces them to take advantage of her religious significance to the men they encounter, who have been conditioned to worship the Lady, but also raises difficulties, since men do not see the aspects of the Lady as human like themselves, making them inevitably suspicious of Birana's human weaknesses. There is, after all, the possibility that she could be the embodiment of an evil spirit sent to test or tempt them. Further problems arise from the fact that men are conditioned to seek "Pleasures" with female aspects as a "Blessing" from their Goddess. As they move from place to place seeking the Refuge, it becomes increasingly difficult for Arvil, who soon learns the truth about women from Birana, to protect her, and to resist his own desire for her, despite his dawning compassion and love for her.

The relationship between Arvil and Birana is the second thread Sargent explores. Both were raised in homosexual cultures, but Arvil is conditioned to think of virtual Pleasures with aspects of the Lady as superior, and as an adjunct to religious worship. Birana, on the other hand, is conditioned to be disgusted by the idea of heterosexuality, and to think of men as dirty violent beasts. Both young people go through serious psychological contortions in coming to realize that their world-views are based on lies. The science fictional set-up thus allows Sargent to examine the development of a romantic sexual relationship from the perspective of a couple with no experience or expectations in regard to such relationships, inviting readers to look at what we might think of as rather mundane relationship dynamics from a new perspective.

I found the ultimate "message" of the novel to be ambiguous, but satisfyingly so. Based on Pamela Sargent's reputation for promoting feminist science fiction (she edited the first all-woman anthology, Women of Wonder, in 1975, laying out her view of science fiction as an ideal tool for exploring feminist ideas and cultural possibilities), I thought there might have been more on a focus of the feminist "utopia" of the women's cities, but this is a secondary aspect of the novel. Through building the cities and expelling men, the Mothers did create a pleasant and peaceful society that is shown as having endured for centuries. Yet, it is also made clear that not all is well in paradise. Rebels like Birana and her mother are occasionally exiled, and others, like Laissa and her mother (who, early in the novel, is emotionally distraught at the duty of expelling Laissa's younger brother when he becomes old enough) have doubts about rightness and the continued viability of their society. It is shown repeatedly that the cities have stagnated, maintaining technologies and customs from the past, but never progressing. And, of course, the entire edifice is based on the "original sin" of forcing the men into a Stone Age existence without access to the comforts and technologies that the women take for granted, and where those bands who attempt strides toward any type of economic or social development are hunted down and murdered by the Mothers' ships.

As is always the case when one group subjugates another, those with the power justify their actions be dehumanizing those whom they subjugate. Birana is genuinely shocked by the fact that Arvil is capable of more than violence and lust, and is intelligent enough to overcome his religious teachings and understand her explanations of how the world really works. Yet she also sees that the men outside the city are usually violent and cruel, and are quite likely to subjugate women when given the opportunity and relieved of their religious belief in the Holy Lady.

There is a hint (though only that) of the possibility of reconciliation. The philosophy of the Mothers may have been a practical one in the aftermath of a war that nearly destroyed humanity. With men out of power, peace and prosperity did prevail, but only for half the human race. In telling the story of Arvil and Birana—a story the women of the city would have previously thought impossible—Laissa raises the possibility of another step forward for their society.