![]() Mattastrophic

Mattastrophic

2/15/2013

![]()

What if your guilt was visible for everyone to see? Suppose your crimes actually granted you special powers, like some inverted superhero story. Would the powers be worth being set apart from the rest of humanity, or would the magic only make that isolation worse?

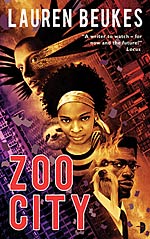

Zoo City, winner of the 2011 Arthur C. Clarke Award, follows former journalist Zinzi December. Zinzi has been isolated from much of humanity due to the baggage she carries: a lingering drug habit, massive debt to her dealer, a bad email scam habit, guilt for her brother's death, and a sloth. Zinzi is one of the animalled, or a "Zoo," and her sloth marks her as a criminal. Her connection to her sloth is magical, granting her the power to find lost things. It's also terminal, meaning that when she or it dies the Undertow will come for her and literally drag her kicking and screaming into the dark.

Zoo familiars come in all forms--mongooses, snakes, tigers, monkeys, scorpions, etc.--with a variety of special gifts and powers. In Johannesburg, South Africa, they are segregated into a run-down ghetto called Zoo City (based on the "gray area" of the Hillbrow district of Johannesburg). Shunned by most normals, Zoos have to get by however they can. Zinzi, playing the Marlowe-esque character, is hired by a reclusive music executive to find the female half of a pair of twin teenie Afro-pop stars. The problem is she doesn't find lost people, only lost things, and her problems are compounded by the shadiness of her employers. Her search will find her combing the dregs of Johannesburg and Zoo City, making connections with the shattered remains of her former life, struggling to cope with her debt and her flaws, all the while with Sloth on her back, non-verbally chiding her.

What Zoo City does well

The most engaging aspect of Zoo City is the way that the animal-magic novum intersects with the setting. The specter of Apartheid is pervasive, even though I can't think of a specific instance in which it is explicitly invoked to add to the ambiance. Zoos are crowded into a run-down ghetto where they have to pretty much fend for themselves. Work is scarce, utilities are slapdash, and gangs of Zoos rove the streets at night. The wonder of the menagerie of animals bonded to humans and the powers they grant is a kind of tarnished beauty as we see the broken lives this phenomena has created. The animal familiars made me very interested in learning these characters lives and just what they did to become bonded to their creatures. The novum feels believable and thankfully does not use the often-appropriated cliche in American tales of secret government agencies looking to weaponize these animalled people. Instead, these feel like real people trying their best to get by, and not revolutionaries or super heroes since this is a book that rejects the traditional notion of heroism from the get-go as it is the criminals, the underclass, that are branded with animals and powers. This, along with the way the zoos and their powers are likened to totemic traditions in traditional African magic and medicine, creates some very interesting tensions throughout the novel: the ghetto and the modern metropolis, the relativity of innocence and guilt, magical power and social power, technology and mysticism, the natural world (animals) and the man-made jungle (the city), etc.

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the back-stories of the various zoos we are introduced to, their animals, and their abilities, are very interesting fare. The Zoos have a variety of psychic powers, like finding things, slipping through locked doors, emotional vampirism, and others. Despite these powers, there are significant drawbacks, as demonstrated by how Zinzi is often overwhelmed by the visions she has of people's lost possessions. Also, if a Zoo is separated from his or her animal, there is a pretty severe mental and physical toll on both of them. Then there is the whole being-dragged-off-to-hell thing if the animal dies. Some think being a Zoo is cool, others that it is disgusting. Some are understanding, and others only pretend to be in order to exploit the powers of the animalled. All in all, the Zoos feel like real people, as do the people who love, fear, understand, and/or revile them.

I found Zinzi to be a good protagonist in that I'm not sure whether I like her or not, and this isn't due to a lack of character development. She follows the traditional hard-boiled detective type: down on her luck, relationships are a mess, on the verge of being completely broke, distrusted by the authorities, distrustful of her employers, etc. I have seen lots of characters in this mold that are crafted to be instantly sympathetic, but while I do sympathize with Zinzi there are also parts of her personality I do not like. Her participation in a network of email scams had me livid due to my considerable experience with spam email and phone calls (may all scam-artist telemarketers be taken by the Undertow). She is a mixed bag of selfishness, neuroses, mixed-up guilt, indignation, good intentions, fear, etc., and I'm fine with not being sure if I like her or not. She reads like a genuine mixed-up, messed-up person, not an archetype. The world she lives in is morally complicated, so why shouldn't she be as well?

Beukes includes a lot of pop fashion and media stuff in the book. Some of it went over my head, but I did enjoy little interludes like the website comment board discussion of a documentary of one of the first noted Zoos in the world (a middle-eastern terrorist/warlord who toted a penguin in a flak jacket with him).

Where Zoo City could have been better

I like hard-boiled detective stories, but like a lot those stories, sadly, I was more interested in the depiction of the world and the narrative language itself than I was in the central investigation. I had a hard time caring about the lives of Sbu and Song, the aforementioned Afro-pop stars. Their lives were part of the hip lifestyle of the rich and famous and the stuff of reality TV, it seemed. I had a hard time getting into their stories and caring about them as characters. The ghetto of Zoo City and it's people seemed oh-so-much-more engaging.

I also found that I would have liked more of a focus on the powers, such as more examples of other people's abilities and how they work. We see a few in some detail and glimpse more, but it left me feeling a bit unsatisfied considering just how big and dynamic this novum was. I believe that is because Beukes wasn't trying to make the powers themselves drive the story, which I understand.

Concluding Thoughts

The Guardian's review of Zoo City provides an interesting link between Zoo CIty and cyberpunk:

Recommended as "very, very good" by William Gibson, this is the other face of cyberpunk, a face we've seen too little of in the past decade. Not the ultra-violent übermensch "future noir" (though there's plenty of violence) but an information-drenched world that has become haunted. Thus the "animalled" may simply be a marker, like the Voudun in Gibson's work, of the strangeness of postmodern modes of being. But true to the king of cyberpunk's original code, this isn't about exposition. Zoo City is about surface, décor and incident, grungey eyekicks and jive-talk for the in-crowd.

I think there is a lot of truth in this characterization of the novel, and a good indicator of how to enjoy it. The book really works that feeling of postmodern cultural saturation and societal defamiliarization and alienation. Like a lot of cyberpunk, though, some readers may characterize Zoo City as mostly style and surface. I teetered on this line since I wasn't quite moved by the core investigation plot that ostensibly drives the novel's action, but I found enough in the novel's novum, it's setting, and the crazy mixed-up life of Zinzi December to appreciate it as a whole.

Score: 4/5

http://www.strangetelemetry.wordpress.com