![]() jynnantonnyx

jynnantonnyx

10/24/2012

![]()

(This review was originally posted on the WWEnd blog: http://blog.worldswithoutend.com/2012/10/it-by-stephen-king/.)

It’s always interesting to look at the stats on the WWEnd site, to see where visitors come from, what pages they like, how long they stay, and which areas are most popular. As it turns out, the most popular page on WorldsWithoutEnd.com is the novel page for It. While It is obviously a well-read novel—87 members have marked it as read, and 53 have rated it—the book remains unreviewed on our site. I thought that odd, and decided to make it a project for this year’s Month of Horrors to read and review Stephen King’s popular book. At 1090 pages, this was a daunting task, but King’s prose is rarely difficult to read, even if his subject matter is often repulsive, and I managed to complete it in about two weeks. After finishing this brick of a book, I think I have a better sense of why it’s as well loved as it is. That doesn’t mean I particularly love it, myself, but I think it might be constructive to explore why I do not. (Some revealing spoilers ahead, be warned.)

The first thing that strikes the reader is the attempted universality of the novel. The town of Derry, Maine is a world unto itself, and this story is as much about the town as it is about the protagonists and their monstrous predator. I’m reminded distantly of Eliot’s Middlemarch, which also created a world within a fictional village; but of course the similarities between the two novels ends there. Derry seems to represent all of America, or at least all of small-town America. Not only that, but the narrative eventually takes the reader outside of the universe and briefly explores the geography of the cosmic space surrounding creation, as filtered through King’s peculiar spiritual philosophy. By the end if It, I felt that Derry was a place I had visited, and about which I had vivid if not fond memories.

The Derry inhabitants depicted are also diverse enough to be close to a universal representation. Children and adults, married and bachelors, sane and insane, poor and rich, bullies and bullied: all these and more have their stories told. If there is any main protagonist it is Bill Denbrough, the boy whose younger brother’s violent and mysterious murder starts off the novel, and who (unsurprisingly, considering King’s usual tropes) grows up to be a horror novelist. But Stuttering Bill takes a back seat for much of the novel, and there are huge sections where you almost forget he’s even there. One gets the sense of having met the entire town by the time it is drowned in the climactic flood.

It also spans an unusual amount of time: 27 years in the main narrative, but counting flashbacks those years arguably number in the millions. We see not only the terrible history of the titular monster, but also the dark and disturbing events that shaped the town of Derry, and, more intimately, the changes that occur in individual lives between childhood and middle age. Even though I find some of King’s observations about human nature to be unlikely, he still possesses enough insight to keep the reader intrigued.

All this to say that there is a good reason It is one of King’s most popular novels. It serves stylistically as a template for many of the novels that followed, and in his ever-expanding shared universe of stories It and its setting of Derry serve as a central narrative hub.

But is it worthwhile in a way that lives up to its hype? Maybe no book can live up to its hype. Maybe we should simply look at It as a horror novel, and see whether or not it works as a member of a genre family. I’m honestly not sure that it does.

Am I saying that It is never frightening? No, there were a few times when I had to put down the book and check down the hall to confirm that no monsters were lurking in wait. Unfortunately those times were few and far between. As suggested above, the bulk of the novel is focused on world building rather than suspense or fear. A great list of disturbing things occur, but too many of them are recounted with emotional distance—there is not enough of a felt, imminent presence of the terror that must have been felt by the characters. I suppose one of the points King is trying to make is how blithely people can accept horrors in real life, how easily people turn off the television when the newscaster talks about a brutal murder, or how some willfully turn a blind eye to violence in their very midst. That’s fair as social commentary, but I think it’s more likely to generate a feeling of concern rather than fear in the reader.

Still, there are plenty of scenes formed around the predator-prey dynamic in the novel, and these are usually the bread and butter of the horror novelist. Nothing scares someone like the thought that something with big teeth and a growling stomach is waiting just behind the next corner. How odd is it that even some of It’s brutal murders are experienced by the victims with a sort of clinical detachment, and punctuated by the absurd monster-movie forms It takes whilst attacking its victims. Later when the Losers Club (the band of children sworn to destroy It) winds their way through a house haunted by It, the entire place is turned into a mostly harmless funhouse in order to frighten the children, and by the time It physically appears the element of tense horror has already been lost. I think I could count the truly frightening scenes of this 1090-page novel on one hand.

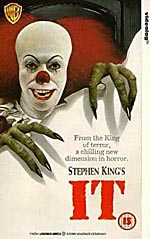

On that note, I have to wonder why people have come to think clowns are scary. I grew up watching Bozo the Clown, and loved his show. Even though the 1990 miniseries adaptation of It gave me nightmares, it never gave me a special fear of clowns. King was apparently playing off of serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s habit of dressing as a clown to lull his victims into a false sense of security, but the popular “scary clown” trope really seems to have started with King. I suppose clowns are scary if you give them sharp teeth and an appetite for children, but there’s nothing scary about Bozo. Clowns can make effective monsters precisely because that’s such a dramatic reversal of what they actually are, but when the popular expectation is for a clown to be a killer, then the entire paradigm is lost. I long for the day when clowns bring a smile to children’s faces again. But I digress.

Another problematic narrative choice is to give It’s perspective of the story towards the end. Considering what It is revealed to be, I find it difficult to believe that the monster could have so much trouble with a group of schoolchildren. “If only it hadn’t been for those pesky kids,” I imagine It saying, fist pumping in the air, “I would have gotten away with the whole thing!” The suggestion is floated by one of the Losers after some library research that It is a mischievous and predatory spirit from ancient American Indian myth, which can be expelled from the world by a mystic ritual. What we eventually learn is that It is in fact a cosmic entity akin to a turtle-like demiurge who created the universe, and that It entered our world partly to ease its billion-year boredom by hunting and consuming the animals of our universe. Both cosmic entities apparently came from a greater entity called only “The Other” (I suppose King has forgotten how to spell “God”), who intervenes in the Loser Club’s lives in a helpfully providential way. Once we read the summarized story from It’s point of view, one can hardly take It seriously as a credible threat. That something so big could be so incompetent as to be killed by a group of children when it had plenty of opportunities to kill them first was a head-scratching revelation. I wish King had left It’s origins and inner thoughts a mystery. Sometimes less is more, even in a sprawling novel like this.

The Losers themselves are the best part of the book. The seven children chosen to destroy It are flawed and likeable, and they are all either troubled from their home lives or from the malign influence of Derry. As adults, some have matured out of the weaknesses of childhood better than others. I expect King is making the point that, even when we are given moments of clarity at malleable times in our lives, we often choose to perpetuate familiar errant behaviors rather than make the effort to change for the better. Perhaps this is a statement about free will? Either that, or a statement about our unwillingness to engage our power to choose. It would take too long to expand on the different characters and their place in the story, but suffice it to say that I kept reading the novel largely for their sake, and not for the horrific suspense.

More disturbing than the Crawling Eyes or Teenage Werewolves was the—how shall I put this?—“bonding ritual” that the Losers perform after their first battle with It in the monster’s lair. I won’t go into detail, but this was probably more sick and twisted than anything else that happened in this novel, despite being presented as a good and noble thing. I’ll just say that it’s a good thing the children started losing their memories soon after they did this.

But overall, would I recommend It? I don’t see how I could not. Despite its flaws and questionable choices, It is a milestone in the history of horror fiction, and I think it’s a key to understanding many of King’s other novels. The book also includes nostalgic retrospectives of the monster movies of old, as It chooses their forms to terrorize many of its victims. As a fixed point in genre history, It cannot be escaped… no matter how fast you run.

http://www.worldswithoutend.com/